Littleberry Adams arrived in the Tennessee Valley a comparatively wealthy man. With seventeen enslaved people in 1809, he and his family easily ranked as the wealthiest members of local white society. Had the Broad River planters not arrived in larger numbers later that year then the Adams family might have kept their position at the top of the local hierarchy.

Due to this affluence, and associated early influence, Littleberry Adams, sometimes known as Little B. in court documents, deserves mention in any early history of Madison county. As such, Daniel S. Dupre makes quick reference to Adams as an example of a successful early squatter in his fantastic book Transforming the Cotton Frontier: Madison County, Alabama, 1800-1840.

Dupre briefly alights upon both Adams’ role as an enslaver of people and early entrepreneur before moving forward with his discussion of north Alabama history. In his citations for the book he references an early court case in Madison county, where in 1810 a man named Robert Beaty sued Adams over delinquent payments for a keelboat with which to haul cotton. Although glossed over in Dupre’s account this case is as informative as it is hilarious; as it highlights not only the cash poor frontier economy of the territorial period but the role of equity and common law in early Alabama legal history.

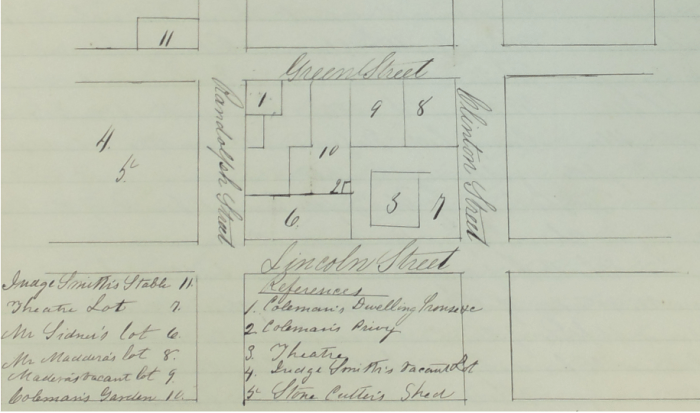

On January 10, 1810, Little B. and Robert Beaty* met at “Dittoes Landing” to sign a contract for “one Keelboat, six polls, four oars, one hammer, [and] one corking chisel all in good order,” for either $120 or $220, depending on who you asked, in increments of fifty cents a day between January 10 and April 1, followed by the rest of the payment upon Adams’ return from the Texan cotton markets.

However, this is where the dispute arose. For although the contract itself mentions the $120, Beaty contended that they made it “in great hast at the boat landing” and that $220 remained the original price agreed upon by all parties. Beaty produced a man named David Thompson, mentioned as the original witness to the contract, who confirmed this differing price.

Adams not only neglected to pay the difference but had gone a solid year since that contract without paying Beaty any of the aforementioned money for the keelboat. As such, Beaty turned not to the common law, which would discount the oral testimony of David Thompson, but towards the newly established courts of equity where his case might be tried “in tender consideration… [for] mattes of fraud, deception, and such mistakes are properly cognizable and relieveable.”**

Both men mustered their attorneys and exchanged barbs over their contract. Littleberry Adams contended that their original contract was “informal” at best and not a binding covenant. While Beaty railed against his non-payment. Finally, in March of 1812, Adams admitted that the original verbal contract stipulated that he pay Beaty $220 for the keelboat.

Yet he still claimed that he ought not pay the total amount. Adams knew that the oral testimony of witnesses doomed him to a lighter wallet, so he decided that everyone should go down with him. He claimed that the boat was faulty and “in consequence of its leakiness the defendant was detained considerable time on the river.” By the time that Adams reached his destination, which appeared to be the Sabine River – a neutral territory between the United States and Spanish America that now forms the border between Texas and Louisiana, the boat began sinking again and he paid two dollars and “a considerable quantity of whiskey,” to have it both caulked and “laid high and dry,” during the repair process.

Littleberry Adams considered the associated expenses sufficient as the Neutral Ground, the territory around the Sabine River, existed as a haven for outlaws and bandits, and any time not spent on the relative safety of the boat probably exposed his small cotton shipping expedition to these dangers. Due to Beaty’s negligence, Adams found no reason to pay him the full price, or really any money at all.

Obviously this argument failed to hold up and Obadiah Jones, that lonely frontier judge, declared that Little B. owed The Beat $220 for the boat and an extra $22 for the court costs.

citation:

Robert Beaty v. Littleberry Adams, Book A, 1-3 (1811)

*Who I desperately want to refer to as The Beat.

**This is legitimately like the first court case ever prosecuted in Madison county, so Beaty is going out on a limb here.