For three days in March their little war raged across the county.

The McMahans and Gibsons arrived in north Alabama and started feuding with each other almost immediately. Neither family appeared on the 1812 Tax List; although John McMahan, as the head of his clan, showed up as a taxpayer in 1815.*

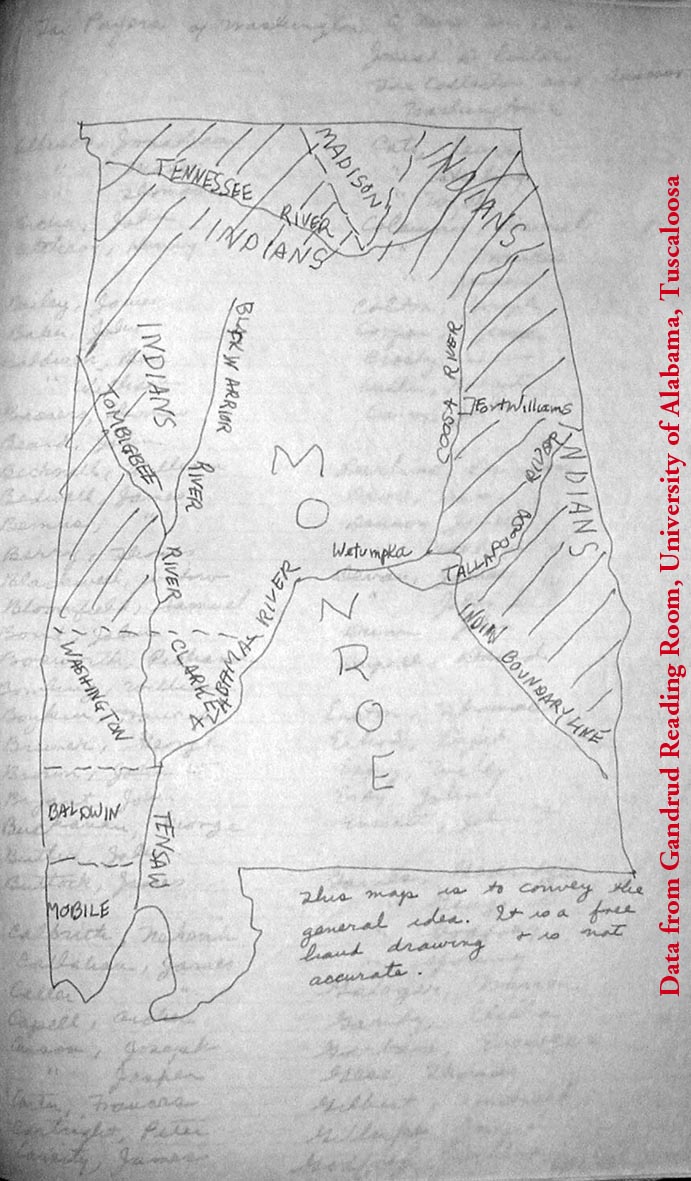

Additionally, the 1816 Mississippi Territory Census appears to have eschewed Madison county entirely. It focused instead on the wild and silent places of what would become the state of Mississippi and upon Monroe county in Alabama. Which, to clarify, in 1816 is all of Alabama aside from the earlier counties of Madison, Washington, and Clarke and the recently conquered Mobile and Baldwin.**

In addition, the transitory nature of the time period, combined with the fact that several of their members died in Madison county, means that either family is unlikely to appear on the 1820 census. So, unfortunately, the motives of either group remain unclear. We are forced to extrapolate.

All that is known is that it started with a simple assault.

On March 7, 1816, William Gibson and Philip Fields found William McMahan. McMahan was alone, possibly in his family’s fields, and they saw their chance. With quick wit and cruelty they both fell upon him.

Three days later the McMahans took revenge. They gathered their allies Henry Seeman and Barnet Hicklin, and together with them the brothers McMahan: John, the injured William, and Martin, all descended upon Robert Gibson while he was unawares. They did “riotously, beat, bruise and illtreat,” the Gibson man before moving on.

Both of these assaults took place in Madison county proper, although the court documents fail to mention where, but the action probably took place along the eastern edge of the county. We can infer this because the action soon moved across the border into the Cherokee Nation, on the northeastern edges of the Mississippi Territory.

Perhaps they heard of planned retribution by the Gibson family. Perhaps they simply had business among the Ani Yun Wiya.*** Lack of the appropriate census data combined with the early Scots-Irish predilection for marrying into prominent southeastern indigenous families means that the McMahans themselves could have been Cherokee people.^

Either way it appears that William McMahan took part in the assault on Robert Gibson and then immediately set out for the Cherokee lands to the east. We know this because later that day he was murdered.

Byrd Ashburne and John Pate waited for him inside the Nation. Their involvement complicates the tale. They either heard of the assault on Robert Gibson and made a unilateral decision to strike at William McMahan or they previously knew that William would go into the bounds of the Cherokee Nation at a specific time and had no qualms about laying in wait for him.

Which means that the original assault by William Gibson and Philip Fields was probably a bungled assassination. If this theory is correct then some spark united the Gibsons, Ashburne, and Pate in their hatred for William McMahan. It is a great shame that so few documents survive from this conflagration.

Either way they shot him from behind. John Pate recognized William McMahan and called out to Byrd Ashburne, who grabbed a musket which he “did shoot and discharge.” The bullet penetrated William McMahan “about an inch on the left side of the backbone.” The two men apparently fled after shooting him because William languished for three days, sliding slowly into death. He managed to communicate the details of his assault before demise.

Obadiah Jones barely knew what to do. They all crowded into his court room on the same Monday in May. Jurors for each case waited with all the patience of lawful busy men ready to make “true deliverance… between the Territory and the prizoners at the bar.” Justice had to be swift.

William Gibson received a twenty dollar fine for his assault on William McMahan and Philip Fields a five dollar fine for participating. A jury fined John McMahan nine dollars for beating Robert Gibson. Whereas they found Barnet Hicklin guilty of $50 worth of assault. Martin McMahan and Henry Seeman were acquitted on all charges. Byrd Ashburne earned a $25o fine, a manslaughter charge, and four months “in the prison of said county.” While John Pate walked away from the whole fiasco a free man.

Of course the Territory dropped the case against William McMahan.

citations:

The Territory v. William Gibson, Minute Book of Madison County Mississippi Territory of the Superior Court in Law and Equity, 1811-1819. p. 189/153-191/154 (1816).

The Territory v. Philip Fields, Minute Book of Madison County Mississippi Territory of the Superior Court in Law and Equity, 1811-1819. p. 192/155-193/156 (1816).

The Territory v. John McMahan, Minute Book of Madison County Mississippi Territory of the Superior Court in Law and Equity, 1811-1819. p. 195/158-197/159 (1816).

The Territory v. Barnet Hicklin, Minute Book of Madison County Mississippi Territory of the Superior Court in Law and Equity, 1811-1819. p. 198/160-198/161 (1816).

The Territory v. William McMahan, Martin McMahan & Henry Seeman, Minute Book of Madison County Mississippi Territory of the Superior Court in Law and Equity, 1811-1819. p. 200/162 (1816).

The Territory v. Byrd Ashburne, Minute Book of Madison County Mississippi Territory of the Superior Court in Law and Equity, 1811-1819. p. 201/163-204/166 (1816).

The Territory v. John Pate, Minute Book of Madison County Mississippi Territory of the Superior Court in Law and Equity, 1811-1819. p. 204/166-209/169 (1816).

*It is not at all unlikely that the McMahans or Gibsons were simply too poor to appear on a tax list, or simply got looked over during the process, for we know that John McMahan previously appeared as a pig thief.

**James Wilkinson literally just took it from Spain in 1813. Marched an American army into the city and said “this is Yazoo Land ceded to us by the Treaty of San Lorenzo.”

***One of several endonyms used by the Cherokee Nation. I threw it in here as a gentle reminder that we usually learned the names for an indigenous group from their enemies.

^The obviously Irish surname does not disqualify them. The famous Muskogee leader Hoboi Hili Miko was better known to white society as Alexander McGillivray; while his nephews William Weatherford and William McIntosh both led opposing forces during the Red Stick War, but their Muskogee troops knew them as Lamochattee and Taskanugi Hatke respectively. The early southeast witnessed far more race mixing than it was comfortable admitting.